What Were the Hairstyles for Women in Ancient China? — From Liao, Jin, Yuan Dynasties to The Republic of China Period

Hairstyles have evolved over time to become more than just symbols of beauty; they also reflect social status, cultural background, and the changing tides of history. In our previous posts, we’ve explored the history of women’s hairstyles in ancient China from the primitive era to the Song dynasty. In this blog, we’ll uncover the development of women’s hairstyles from the Liao, Jin, and Yuan dynasties to the Republic of China, delving into the stories behind each style and the era they represent.

Ⅰ. Liao, Jin, Yuan Dynasties

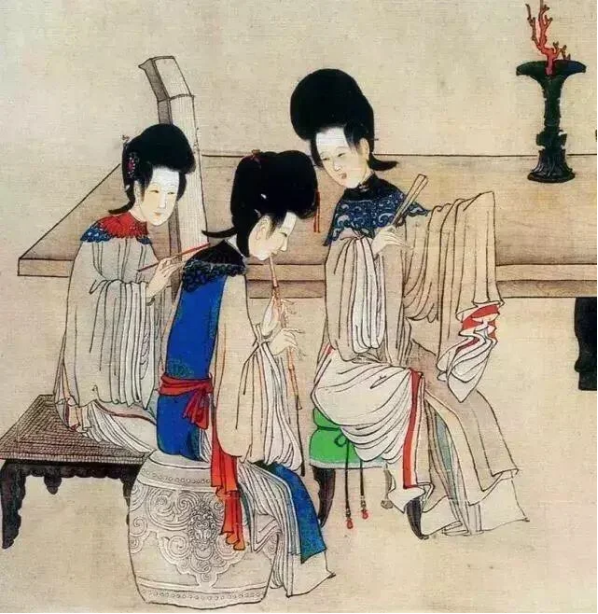

Ling Snake Bun

Hairstyles and accessories during the Jin dynasty were primarily influenced by Han Chinese styles. In the Yuan dynasty, many hairstyles and accessories from the Song dynasty, such as the cloud bun and high bun, remained popular. In the painting Du Qiuniang(杜秋娘图)by Yuan artist Zhou Lang(周朗), the Tang dynasty singer Du Qiuniang is depicted holding a Chinese pan flute, with her hair styled in the graceful and intricate Ling Snake Bun (灵蛇髻). Her hairstyle is adorned with a wide horn-shaped comb, phoenix hairpins, and dangling pearl drops. On either side of her bun, there are flower-shaped hairpins in the form of cloud patterns.

Kun Hair

Kun Hair (髡发), or “shaved hair,” refers to a hairstyle where certain sections of hair are shaved or cut off. In simpler terms, it can be likened to the “balding” or “Mediterranean” hairstyle. This style includes, but is not limited to, leaving long locks on either side of the forehead, or shaving other parts of the hair into round, triangular, or crescent shapes. In some cases, two long locks might be braided.

The Liao dynasty, established by the nomadic Khitan people, had a distinctive hair tradition. The Khitan were a pastoral people, moving with the grasslands, and relied on fishing and hunting for survival. To keep their hair out of the way while working, they often shaved parts of their heads, leaving the remaining hair sometimes braided. This hairstyle became a standard look for Khitan young men. The Khitan artist Hu Kui’s painting Zhuoxie Tu(胡瓌,《卓歇图》) reflects the male hairstyles of that time.

In the past, women were required to wear this hairstyle before marriage, but after marriage, they would grow their hair out and style it into a high bun on top of their heads. In the known Liao dynasty murals, Khitan women are typically depicted with Kun Hair, where the hair at the front of the scalp was shaved off.

Wrapped Head

Wrapped Head (裹头) was not a style exclusive to the Song dynasty; it was also popular in the Yuan dynasty, becoming a common everyday look. Women in the streets often wrapped their heads in cloth. In the Yuan dynasty, Wang Feng’s Pu Dong Nu (王逢,《浦东女》) describes a woman: “A piece of blue cloth wrapped around her head, barefoot as she pedals the cart, splashing through the water.”(一方青布齐裹头,赤脚踏车争卷水。)

Ⅱ. Ming Dynasty

Yi Wo Si

The hairstyles of women in the Ming dynasty, while not as varied and colorful as those in the Tang and Song dynasties, still featured various styles. One popular style was the “一窝丝 “ (A Nest of Silks). This style involved gathering all the hair into a round, cloud-like shape without braiding or tying it up. Sometimes, the hair was secured with a silk net, called a “zan,” (瓒) and further adorned with additional hairpieces or special buns.

Di Bun

The Di Bun (狄髻) was a type of headdress worn by married women in the Ming dynasty for formal occasions. It was typically made from materials like silver threads, gold threads, rattan fibers, and natural hair. The headdress was often covered with a layer of black gauze and shaped like a cone, sitting on top of the bun on the head.

In the Ming dynasty, women’s hairstyles became notably more modest in height compared to earlier periods. From the mid to late Ming, the shapes of their hair buns shifted from flat and round to more elongated oval forms. To save time and effort, the use of pre-made hairpieces became very popular. Wearing various pre-made hairpieces became one of the main ways for women to change their hairstyles.

Peony Head

The Peony Head (牡丹头) was a hairstyle where women took the fake hairpieces from the Jin dynasty, which were originally worn hanging at the back of the head, and wore them upside down. This created a retro yet innovative effect. The women would style their natural hair into a bun about one foot high, and then use the hairpiece to fill and enhance it, covering their own hair with the false hair, adding more decoration for effect.

Three Small Buns

The Three Small Buns (三小髻) was a hairstyle commonly worn by unmarried young girls. The style involved dividing the hair into three sections, with each section styled into a hollow, ring-like bun. These buns could be placed on the top of the head, on the forehead, or in other areas.

Three-Twist Hairstyle

The Three-Twist Hairstyle (三绺头) was a distinctive and representative hairstyle for Han Chinese women in the Ming dynasty. To style it, the hair on both sides of the temples was divided into two sections, and the hair on the forehead was styled into a third section. The two temple sections were swept over the ears and shaped, while the forehead hair was combed backward and combined with the hair on top of the head. Often, a hairpiece or padding was added to give the style volume, creating a full, rounded effect when viewed from the front. Fan Bingbing’s hairstyle of the Three-Twist Hairstyle paired with this set of Ming Dynasty clothing looks both imposing and classic.

Ⅲ. Qing Dynasty

The variety of women’s hairstyles in the Qing dynasty was extensive, with distinct differences between Han Chinese and Manchu women in their daily hairstyles. The well-known “Qī tóu” (旗头) was a court hairstyle, while there were also folk hairstyles suitable for everyday wear.

In the early Qing dynasty, Han women’s hairstyles and accessories largely followed the styles of the Ming dynasty. A set of exquisite illustrations from the Yongzheng period, titled Twelve Court Ladies, housed in the Forbidden City, depicts women wearing Ming-style dresses and hairstyles. These hairstyles include the huíxīn bun (回心髻), qīngshuǐ bun (清水髻), and the chuí bun (垂髻), among others.

Huixin Bun

Clam Pearl Head

The Clam Pearl Head (蚌珠头) became popular in the late Qing dynasty. This hairstyle featured a pair of luó (螺) buns on either side of the forehead, resembling pearls emerging from clam shells, and was often adorned with hairpins, green pearls, and white orchid flowers. Some variations included long hair flowing down the back, adding to the elegance. This hairstyle was commonly worn by young girls who had not yet reached adulthood, often before they had their coming-of-age ceremony.

Qi Tou

In the Qing dynasty, Manchu women typically wore the “Qī tóu” (旗头) hairstyle, which was distinctive and unique to their ethnicity. Popular styles included the “一字头” (one-line head) and “大拉翅” (big winged head). Meanwhile, Han Chinese women in the Qing dynasty were allowed to maintain their traditional hairstyles due to a special imperial decree, which exempted them from adopting the Manchu style, allowing them to keep their own ethnic hairstyles by wearing Qing dynasty clothing.

IV. The Republic of China

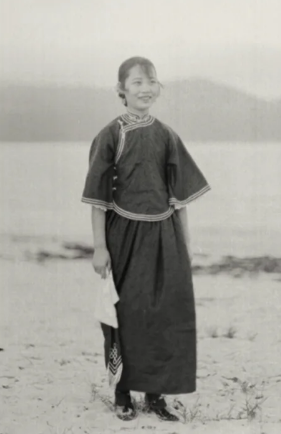

Front Bangs

In the late Qing and early Republic periods, as the feudal society began to collapse and Western culture gradually permeated, traditional hairstyles and decorations evolved towards a more modern, simple, and bright style. While some young women retained traditional bun styles, many began to adopt a fringe of short hair at the front, known as “front bangs.” If we trace the origins of this hairstyle, it can be linked to ancient styles where unmarried women used to cover their foreheads with a lock of hair. By the late Qing, especially after the Gengzi Year (庚子年,1900), this hairstyle became popular among women of all ages. Its most distinct feature is a lock of short hair left at the forehead.

After the 1911 Revolution, the trend of cutting hair became popular. By the 1930s, the practice of perming hair, which had originated abroad, was introduced to China through several coastal trading ports. A small group of high-ranking officials and elites, who sought Western-style perms, set the trend for fashionable hairstyles. At this time, most people began to adopt Western hairstyles, and the influence of Western fashion had a significant impact on Chinese hairdressing, changing traditional ethnic styles. China entered a new historical era, and as a result, people’s hairstyles underwent dramatic changes, transitioning from traditional buns to simpler styles. Women’s hairstyles in the Republic of China can be broadly categorized into two types: the “conservative” and the “reformist.” Conservative women largely followed the late Qing styles, while reformist women fully rejected the traditions of the feudal era, embracing a new, diverse wave of fashion.

Conservative Women

Reformist Women

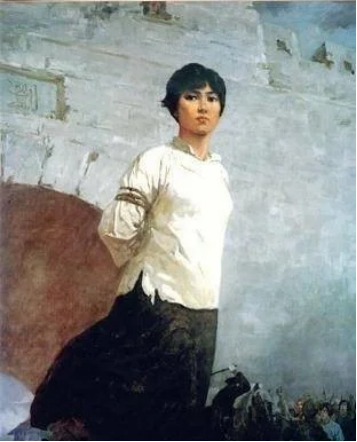

Short Hair

Short hair and gender equality were once a bloody battle in China. For Chinese girls, cutting their hair could even be life-threatening. In the early years of the Republic, women’s hairstyles were strictly regulated: young girls wore double braids, teenage girls kept a single long braid, and married women wore their hair in buns. Society viewed a girl cutting her hair as an act of rebellion. The first recorded women’s hair-cutting movement in China took place in 1912 at Hengcui Girls’ School in Hunan. Influenced by the male hair-cutting movement of the time, student Zhou Yongqi (周永琪) bravely cut her hair and founded the “Women’s Hair-Cutting Society.” However, this movement was seen as a threat to traditional values, with critics labeling it as “gender-confusing and immoral.” The hair-cutting society was quickly shut down by the conservative authorities.

After the May Fourth Movement, with the promotion of gender equality and the awakening of women’s consciousness, the trend of female students cutting their hair was reignited. Yang Kaihui (杨开慧), a student at Xiangfu Girls’ School in Changsha, was the only girl in her school to cut her hair short, and she inspired other girls around her to do the same. However, these progressive young women who embraced short hair as “revolutionaries” often paid a heavy price, sometimes even with their lives. They were sometimes subjected to rape and murder by powerful local figures, and their bodies would be left exposed on the streets after being brutally murdered. This brutal form of death was a warning to women that the authority of society should not be challenged lightly.

This situation didn’t change until the 1920s, when mass culture emerged. The image of Western women with short hair crossed over through films, and female movie stars began to follow suit, making short hair the new fashion trend for modern urban women. It was only when short hair became a rising aesthetic that Chinese women truly regained control over their own hair.

Summary

Looking back at history, Chinese women have only been allowed to wear short hair for less than a century. Whether beautiful long hair is a treasure or a burden is something each person has their own answer to. What cannot be denied is that a woman’s hairstyle directly reflects her aesthetic preferences and social status, while also indirectly reflecting the changing trends of society. As women gain more freedom with the liberation of productivity, their choices in hairstyles naturally increase.

We hope that, just like with hairstyles, women will also gain more freedom in areas such as employment and political rights. A woman’s beautiful hairstyle can please others, but it can also be a source of joy for the active and positive self within.

0 Comments