How Did the Qing Imperial Court Celebrate in the Depths of Winter?

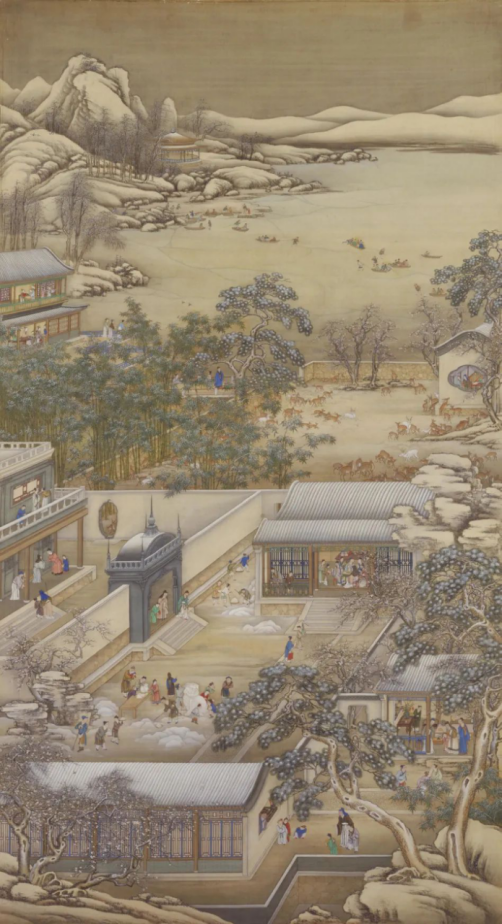

“The cold winter deepens, as snow buries a thousand homes.” In the depths of winter, as the year draws to a close, the Qianlong Emperor’s court created a vivid depiction of the twelfth month in the Yongzheng Court’s Twelve Month Festivities(宫廷画十二月行乐图). The painting captures lively scenes from the Old Summer Palace, such as building snow lions, plucking plum blossoms, clearing snow for travel, and ice-skating with sleds—common winter activities in the Qing Dynasty. In addition to these, more grand winter events were about to unfold.

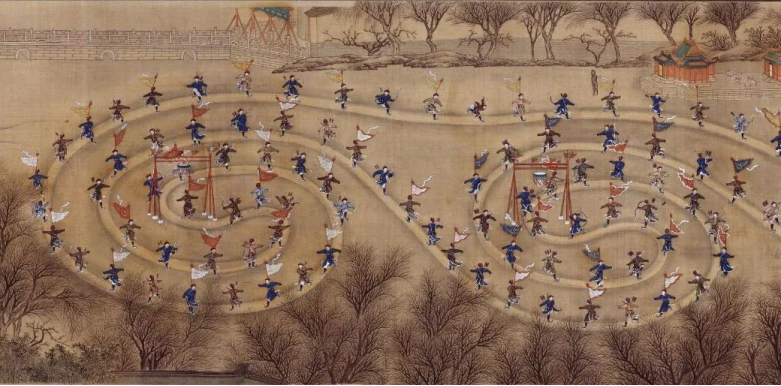

After the Qing Dynasty was established, ice sports gained significant popularity in northern China. Ice-skating, along with archery and horsemanship, became an important national custom during the Qing Dynasty. The sport reached its peak during the reign of Emperor Qianlong. In 1745, Emperor Qianlong wrote the“Imperial Poem on Ice-Skating(《御制冰嬉赋有序》)”, officially naming the ice sport bingxi (冰嬉). The Imperial Household Department’s Ice Sledge Bureau would regularly recruit skilled ice skaters from the Eight Banners to form a performance team. Training would begin after the Winter Solstice and formal competitions and performances were held around the Laba Festival. These events took place on the Taiye Pond in the Western Garden, where the emperor, empress, royal officials, and foreign envoys would all gather to watch. This tradition continued throughout the Qianlong period and lasted into the Guangxu era.

The ice sports during the Qing Dynasty could roughly be divided into three categories: speed skating, ice skills, and ice football.

Ⅰ. Speed Skating

In ancient times, there was a special term called “抢等” (qiang deng), which is described in the“

Records of Imperial Beijing’s Seasonal Celebrations (《帝京岁时纪胜》)”as follows: “The shoes worn for skating all had iron edges, allowing them to glide across the ice like stars racing through the sky, competing for victory. This was called ‘skating’.” The meaning is that the goal was to win by speed, much like a fast-moving object.

Ⅱ. Ice Skills

In ancient times, there was an event called “shooting the sky ball” or “turning dragon ball shooting”, where participants would set up flag gates on the ice and perform archery while skating. This cleverly combined archery and ice skating, as Emperor Qianlong remarked, “Though ice-skating may seem playful, it contains elements of martial skill.”

In addition to this, other ice skills included activities like performing handstands on ice, lifting poles, climbing ice poles, ice martial arts, ice acrobatics, and group ice performances. As the ancients once said, “The skillful movements, like a dragonfly skimming the water or a swallow flying through the waves, are truly captivating to watch.”

Ⅲ. Ice Football

Also known as “Cuoju” or “抢球“, ice football involved wearing ice skates while kicking a ball. Both teams, each consisting of dozens of players, would compete in a fast-paced, high-contact match, resembling modern ice hockey. The “Records of Imperial Beijing’s Seasonal Celebrations(《帝京岁时胜》)“ describes it as: “Ice football, which even the emperor watched, as it was a display of martial spirit.”

Ⅳ. Emperor’s Blessing

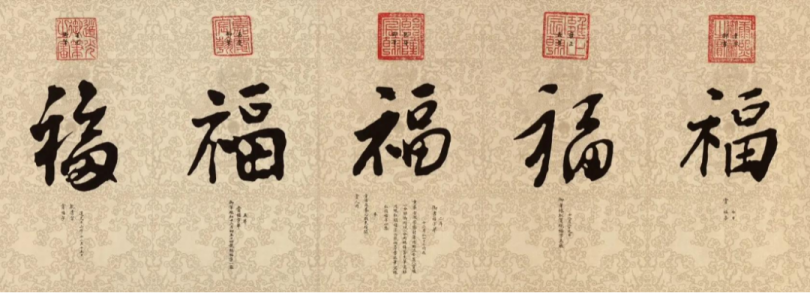

Since the Kangxi era, every year on the first day of the twelfth month, the Qing court would hold a “Beginning of the Year Blessing” ceremony, where the emperor personally wrote the character “福” (blessing) and presented it to civil and military officials, symbolizing the emperor’s wish for “blessings to the people.” Early in the morning, the head eunuch of the Maoqin Hall would prepare dragon-themed paper, large brushes (referred to as the “Blessings to the People Brush”), inkstones, and other materials at Chonghua Palace. After the emperor arrived, he would use the large brush to write several large “福” characters. The first “福” he wrote for the new year would be hung in the main hall of Qianqing Palace, and the others would be posted around the palace and given to the empress, consorts, and officials as gifts.

From right to left are the “福” characters written by Emperors Kangxi, Yongzheng, Qianlong, Jiaqing, and Daoguang.

Starting from this day, whenever provincial governors (such as generals and imperial commissioners) submitted reports or petitions to the emperor, he would include a written “福” character in his response, offering his blessings. Between the fifteenth and twenty-seventh days of the twelfth month, the emperor would summon court officials, guards, various princes, ministers, and Hanlin scholars in batches at Chonghua Palace (or the western warm pavilion of Qianqing Palace) to personally bestow the “福” character upon them.

During the Yongzheng period, at the end of each year, the emperor would personally write the character “福” (blessing). He issued an edict saying, “After the seals are closed for the year and the political affairs become slightly less busy, I write the character ‘福’ and bestow it upon the officials, with all ministers thanking me for granting them my blessings.”

Emperor Qianlong took the practice of writing the “福” character even more seriously. Before writing the “福” character, he would first visit Chanfu Temple to light incense, and then go to Chonghua Palace‘s Shufang Zhai to write the character in large calligraphy. There are many examples of Qianlong granting the “福” character. For instance, Wang Jihua, who served as the Grand Secretary for thirty-one years, received twenty-four “福” characters over the years, which he framed and displayed in a room called the “Twenty-Four Blessings Hall.”

Emperor Jiaqing adhered to the established tradition of writing and granting the “福” character. He once wrote a poetic couplet about the “福” character, stating that besides the first “福” character being hung in the main hall of Qianqing Palace, nearly 20 other “福” characters would be posted around the palace grounds. In addition to the calligraphy of “福,” Emperor Jiaqing also wrote various auspicious phrases in five, seven, and even thirteen-character couplets, such as “Yichun Yingxiang” (宜春迎祥, May Spring Welcome Auspiciousness), “Yiren Xinnian” (宜人新年, Wishing People a Happy New Year), and “Yinian Kangtai” (一年康泰, A Year of Peace and Prosperity), totaling over a hundred examples. These auspicious sayings were posted all over the palace, creating an atmosphere of good fortune and happiness.

As the year-end festivities grew, the Qing palace would engage in various New Year’s customs, such as performing sacrifices to the kitchen god, hanging imperial instructions, dusting off decorations, and honoring ancestors. Once the New Year began, grand performances, festive markets, lantern displays, and fireworks would be held, forming a unique set of traditional customs that celebrated the Spring Festival with distinctly national characteristics.

0 Comments