Exploring the Tang Dynasty Treasures: The Legacy of Hejia Village (Part 1)

Hejia Village, as the name suggests, is a village inhabited by a family with the surname He, a common surname in China. In ancient times, this area in Chang’an was a prime residential area for royal families, nobles, and high-ranking officials. The village became globally known after an accidental discovery at a construction site, which shocked the archaeological community both in China and abroad. Among the items unearthed were over a thousand relics, including gold and silver objects, precious jade and jewelry, valuable medicinal materials, and both Chinese and foreign coins. The large number, high quality, variety, and well-preserved condition of these artifacts made this find one of the most important archaeological discoveries of the Tang Dynasty in the 20th century. Now, let’s take a journey with Silk Divas into this luxurious and mysterious era.

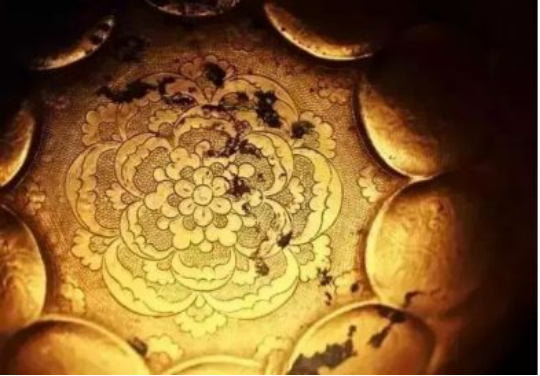

Mandarin Duck Lotus Petal Pattern Gold Bowl

The Lotus Petal Pattern Gold Bowl is adorned with fish egg patterns all over its surface. The outer wall features two layers of lotus petals. The upper layer is intricately engraved with images of rare birds and animals, such as a fox, rabbit, deer, parrot, and mandarin ducks, along with flowers and plants. The lower layer depicts honeysuckle flowers, which were very popular during the Tang Dynasty. According to the Compendium of Materia Medica, long-term consumption of honeysuckle is believed to promote longevity, symbolizing a wish for a long life.

At the center of the bowl’s interior, there is a rose-shaped flower pattern, while the outer bottom of the bowl is engraved with a mandarin duck looking back. Mandarin ducks have long been a symbol of love and happiness, and their pairing with lotus flowers further conveys the beautiful wish for harmony in marriage, eternal unity, and blessings of many children.

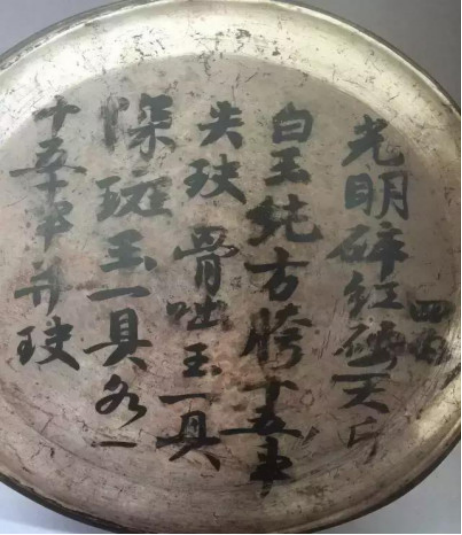

In the Tang Dynasty, gold and silver objects were carefully regulated to prevent trading lightweight items for heavier ones. Each piece was often marked with its weight in ink, and some even had the weight engraved. On the inner walls of the two bowls, the weights are written as “九两半” and “九两三,” which are believed to represent the weight of the bowls.

According to the Tang Code (《唐律疏议》), it was forbidden for non-royal individuals to use pure gold or jade for utensils. This suggests that gold and silver items were primarily used by the royal family and nobility. They were also sometimes given as rewards or tokens of appreciation by the emperor to loyal and successful officials.

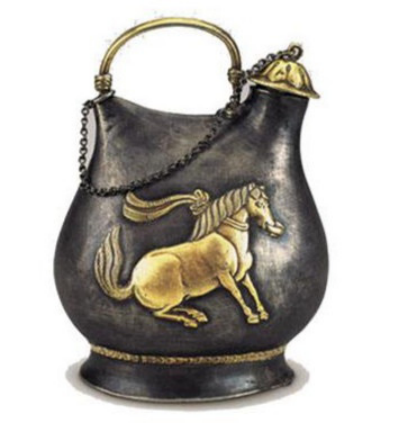

Gilt Dancing Horse and Cup Pattern Silver Pot

The Gilt Dancing Horse and Cup Pattern Silver Pot is one of the 18 national-level treasures housed in the Shaanxi History Museum. The shape of the pot is modeled after the leather water bags used by the northern nomadic Khitan people. This artifact represents the exchange and integration of minority cultures with the Central Plains culture.

If you watched the popular Chinese drama The Longest Day in Chang’an (《长安十二时辰》), you might have noticed this artifact featured in the series. Can you spot it if you take a closer look?

Did you spot anything?

Of course, the most valuable feature of this dancing horse pot is the two dancing horses on its body. During the Tianbao period of Emperor Xuanzong of the Tang Dynasty, on the “Qianqiu Festival,” which was his birthday, grand banquets were held in front of Xingqing Palace. These banquets were attended by civil and military officials, foreign envoys, and leaders of minority ethnic groups. The dancing horses were part of the entertainment, adding to the festivities.

When the music of Qingbei Le (《倾杯乐》) played, hundreds of golden and silver-clad dancing horses would leap into action, raising their heads and wagging their tails in a lively performance. At the peak of the music, the horses would leap onto three-story-high platforms, spinning as if flying. The lead horse would then pick up a wine cup from the ground and carry it to Emperor Xuanzong as a toast to his longevity.

The lines “Bowing and carrying the cup to the celebration, offering heartfelt wishes for endless longevity, and with the final cup at the end of the banquet, dropping its head and tail, drunk as a mud” (屈膝衔杯赴节,倾心献寿无疆,更有衔杯终宴曲,垂头掉尾醉如泥) perfectly capture the lively essence of these dancing horses!

In the fourteenth year of the Tianbao era, a historic turning point occurred during this grand imperial birthday celebration. After the An Lushan Rebellion broke out, Emperor Xuanzong of the Tang Dynasty fled the capital, and the dancing horses were scattered. They ended up in the hands of Tian Chengsi, a general under An Lushan.

One day, during a military banquet, the dancing horses, hearing the music, began to dance in time with the rhythm. The soldiers, mistaking this as some kind of evil omen, beat the horses to death.

The once-popular tradition of the dancing horses offering a cup as a birthday tribute vanished forever with the changes brought about by history. The moment of the horses offering their toast is immortalized on this silver pot, serving as a lasting testament to the rise and fall of the Tang Dynasty.

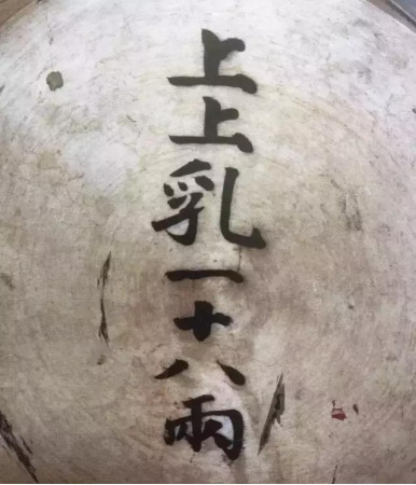

Gilded Parrot-Patterned Silver Jug

This piece is one of the 18 national treasure-level artifacts housed at the Shaanxi History Museum.

The main decorative motif on the body of the jug is a parrot pattern. Parrots, with their vibrant and colorful feathers and ability to mimic human speech, were highly admired by the Tang people. As a result, parrots became one of the tribute items offered to the Tang Dynasty by local regions and neighboring countries.

The empty areas on the jug’s body are filled with a “fish roe” pattern, symbolizing fertility and prosperity. The shoulder of the jug is equipped with a handle. The lid of the jug is inscribed with the words “Purple Quartz 50 taels, White Quartz 12 taels.” Both purple and white quartz are types of mineral substances that were important ingredients in alchemy. The ancient Chinese believed that using gold and silver containers to hold medicinal substances would enhance their efficacy. The medicinal materials found in Hejia Village were all stored in gold and silver vessels.

Silver Box

The silver box features the handwritten inscriptions of alchemists from the time, which hold great value for both calligraphy enthusiasts and researchers of medicinal studies.

Tang Dynasty calligraphy represents a peak in the history of Chinese calligraphy. During this period, various script styles such as regular, semi-cursive, cursive, seal, and clerical scripts flourished. Alchemists’ calligraphy, primarily used for medicinal prescriptions, was mostly written in semi-regular script for ease of reading by the pharmacists, yet it was not meant to be considered an artistic calligraphy piece, giving it a more casual and free-spirited appearance.

The significance of the inscriptions on the gold and silver artifacts from Hejia Village goes beyond just their calligraphic value. The objects inscribed are extraordinary in their own right. Anyone who practices calligraphy knows that writing on gold and silver is much more challenging than writing on paper. The space for writing is limited, yet the inscriptions remain elegant and fluid, showcasing remarkable skill and leaving one in awe.

Red Gold Dragons

A total of 12 pieces were unearthed. Despite their small size, the golden dragons are vividly detailed, with lifelike postures—some are gazing, others are in motion—capturing a natural and dynamic expression. Their horns are naturally curved, and the hair on their brows, eyes, and neck, as well as the dragon scales, are all clearly visible, making them intricate and exquisitely crafted.

In the Tang Dynasty, golden dragons were regarded as auspicious symbols, believed to ward off disasters and evil spirits, while also representing imperial power. There is also speculation that these gold dragons may have been used as ritual tools during Taoist dragon-throwing ceremonies.

The Dragon-Throwing Ritual stems from Taoist beliefs in the Three Officials of Heaven, Earth, and Water. Ancient emperors typically performed ceremonies involving “burial” or “sinking” of offerings, with mountain sacrifices often “buried” and water offerings “sunk.” Early ritual objects for “sinking” included gold, silver, and bronze items. By the Tang Dynasty, a formal ritual of sinking gold dragons and jade tablets had been established. The common practice was to bind jade tablets inscribed with wishes, jade discs, golden dragons, and golden seals with blue silk. After conducting Taoist rites to dispel disasters, these items would be thrown into famous mountains and rivers as a symbolic offering to the Three Officials.

In our next blog, we will continue introducing the treasures from Hejia Village.

0 Comments