How to Style Men’s Clothing in the Tang Dynasty – Men’s Robes (Part 2)

Ⅰ. Introduction

During the Sui and Tang dynasties, China established a sophisticated bureaucratic hierarchy codified into law, featuring a nine-tiered ranking system that governed officials from the imperial court to provincial administrations. This institutionalized hierarchy extended beyond administrative functions, meticulously regulating visible markers of status including ceremonial attire and protocol observances.

The sartorial system for officials evolved into four distinct categories: ceremonial robes for religious rites (祭服), court attire for imperial audiences (朝服), official garments for daily duties (公服), and informal wear for private occasions (常服). While menswear maintained relative simplicity compared to the elaborate fashions of noblewomen, its color symbolism carried profound bureaucratic significance. The chromatic hierarchy transformed garment hues into a visual language of power – where a single shade could denote everything from judicial authority to military rank.

This chromatic codification paralleled European heraldic traditions in its precision, with specific colors reserved exclusively for certain ranks. Imperial edicts carefully prescribed which officials could wear deep purples symbolizing cosmic harmony, vibrant crimsons denoting executive power, or tranquil greens allocated to lower administrative tiers. Such regulations transformed court assemblies into living tapestries of political hierarchy, where a glance at a colleague’s robes immediately revealed their position in the intricate machinery of state.

Ⅱ. What Is Paofu

The robe-style garment, known as paofu (traditional Chinese robe), emerged as a sartorial democratizer in medieval China – worn with equal authority by emperors and embraced by commoners alike. This iconic silhouette dominating character wardrobes in the Netflix historical drama The Longest Day in Chang’an traces its origins to the Northern Zhou dynasty (557-581 CE), blending Central Plains tailoring with northern nomadic influences through its signature round collar and right-over-left fastening.

Ⅲ. Subtle Differences

Distinguished by bordered collars and cuffs, the design evolved practical innovations like the “Panling Lanshan”- a lower hem reinforced with horizontal stitching that became a status marker. Court regulations dictated subtle power differentials: civil officials wore ankle-length versions symbolizing scholarly dignity, while military officers adopted knee-breeching cuts for mounted mobility. The tapered sleeves varied from magistrates’ flowing drapery to soldiers’ functional narrow cuts.

Ⅳ. Robe with Split Sides

After continuous improvement, the robe evolved into the more practical robe with split sides (缺胯袍衫), which allowed greater freedom of movement. It was subsequently popular among scholars, merchants delivering goods, and workers bending over in rice fields. The side slits cleverly combined the wide-legged pants popular in equestrian culture with the dress requirements of Confucian etiquette, reflecting China’s cultural integration.

Much like the Elizabethan doublet’s evolution from military gear to court fashion, the paofu transformed from nomadic riding coat to bureaucratic uniform, its very seams stitching together the Tang dynasty’s multicultural tapestry. The robe’s enduring popularity across social strata made it the medieval equivalent of a bespoke suit – simultaneously standardized yet infinitely adaptable to its wearer’s station.

Ⅴ. Different Rank Distinction

According to the record in “唐音癸签”, “The color of official costumes in the Tang Dynasty was determined by the rank of the official’s position.” In 630 AD (the fourth year of the Zhenguan/贞观 reign) and 674 AD (the first year of the Shangyuan/上元 reign), imperial decrees were issued twice to stipulate the colors of official costumes and the ornaments to be worn. The second set of regulations was more detailed, as follows:

“Officials of the third rank and above, both civil and military, should wear purple robes, with jade – inlaid gold belts consisting of thirteen plaques. Fourth – rank officials should wear dark red robes and gold belts with eleven plaques. Fifth – rank officials should wear light red robes and gold belts with ten plaques. Sixth – rank officials should wear dark green robes and silver belts with nine plaques. Seventh – rank officials should wear light green robes and also silver belts with nine plaques. Eighth – rank officials should wear dark blue robes and belts made of brass (鍮石) – like metal belts with nine plaques. Ninth – rank officials should wear light blue robes and the same brass – like metal belts with nine plaques. Common people should wear yellow clothes and belts made of copper or iron with seven plaques.”

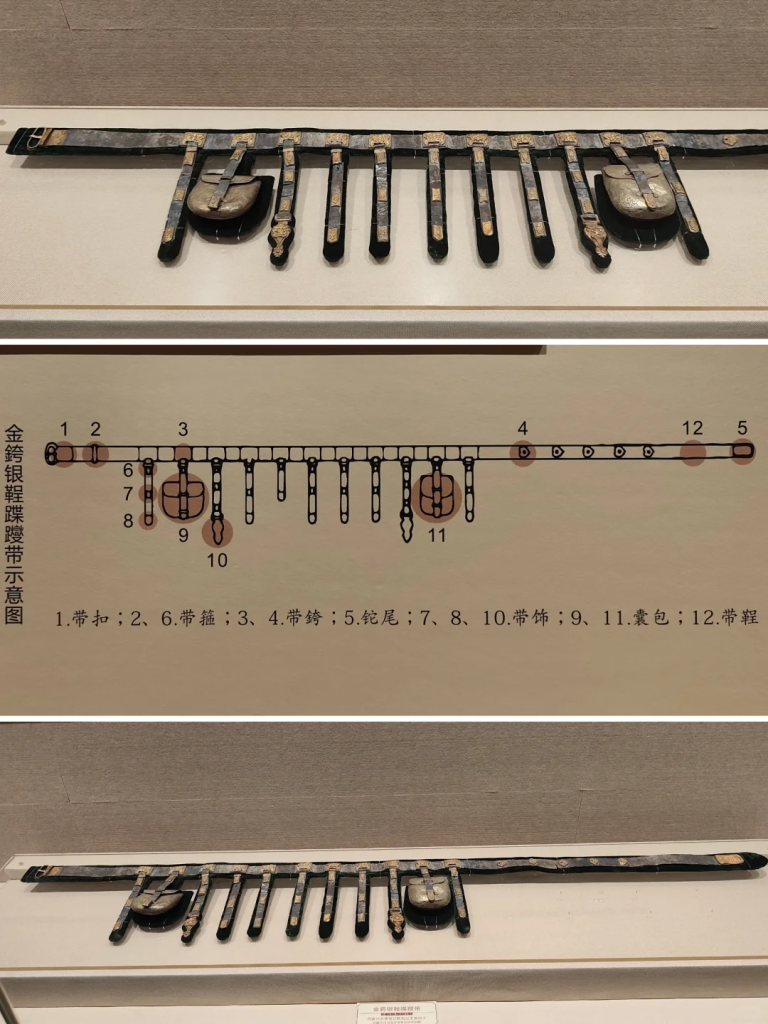

Ⅵ. Dié Xiè Belt

If you’ve been observant, you may have noticed that paofu – style garments don’t have pockets. So, what can one do when they need to carry some personal items around? Well, this is where the belt comes in extremely handy.

The belt is not only a functional accessory but also a decorative one. It can be adorned with belt plaques. Some of these plaques are designed with holes or attached rings. Additionally, a small “蹀躞带” (dié xiè belt) can be hung from them. These design features allow people to conveniently hang daily – use items on the belt. For example, things like small purses, keys, or other trinkets can be easily attached, making it a practical solution for carrying essentials without the need for pockets.

Ⅶ. Example in Dié Xiè Belt

As described earlier, the material of the belt plaques inlaid on the belt varies according to the official’s rank.

Take the jade belt plaques as an example. A jade belt plaque set consists of a belt buckle, belt plaques, a belt strap, and a belt end – piece. The belt buckle and the belt end – piece are similar to the buckle and the decorative tip of a modern – day leather belt. The “belt strap” refers to the leather part of the belt. The belt plaques, also called belt plates, are inlaid on the “belt strap” and come in various shapes such as square and semi – circular.

According to the regulations on the imperial carriages and official costumes in the Tang Dynasty, officials of the third rank and above were permitted to use gold and jade belts with 13 or more belt plaques.

0 Comments