Do You Like the Textile Patterns of the Song Dynasty?

The Song Dynasty, which was divided into the Northern Song and Southern Song periods, was one of the most prosperous eras in Chinese history in terms of economy, culture, and technological advancements. Politically, it prioritized civil governance over military power. The economy was highly developed, commerce flourished, and the arts thrived, with notable achievements in Song ci (poetry), painting, and innovations such as the Four Great Inventions.

If you were to travel back in time to the Song Dynasty, you would notice that men typically wore round-collared robes in simple colors like black and white, with minimal patterns. Women’s clothing, such as ruqun (襦裙, a blouse and skirt ensemble), featured elegant and subtle colors, often adorned with floral or bird motifs. The designs emphasized refinement and modest beauty.

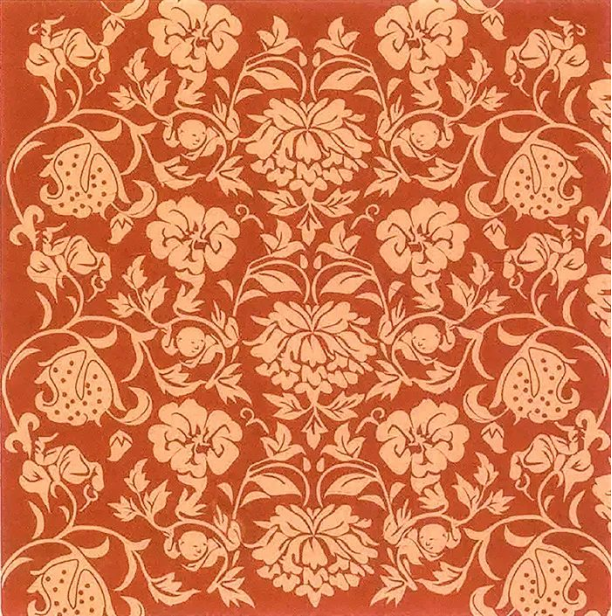

Textile production was widespread across different regions, each known for its distinctive silk fabrics, including brocade, damask, gauze, and satin. The Song Dynasty’s textile patterns had a unique aesthetic that reflected the era’s artistic sensibilities. Unlike the bold and extravagant motifs of the Tang Dynasty—often featuring large flowers and fierce beasts—Song Dynasty patterns were more delicate and naturalistic, influenced by the refined tastes of scholars. While Tang designs exuded opulence and grandeur, Song patterns embodied a softer, more organic beauty.

Ⅰ. Plant Motifs in Song Dynasty Textiles

Lu You, in his Notes from the Lao Xue An Bi Ji (陆游,《老学庵笔记》), wrote:”Seasonal decorations include spring banners (春幡, It is a banner that is hung on the treetops on the Beginning of Spring day or when spring banners are put up, signifying the welcoming of spring. ), lantern balls, dragon boat races, mugwort tigers, clouds, and the moon. As for flowers, peach blossoms, apricots, lotuses, chrysanthemums, and plum blossoms together form a complete scene, representing the beauty of the entire year.”

In the Song Dynasty, floral motifs were not only popular among women but also widely embraced by men. It was common for men to wear floral hairpins, a practice documented in historical records and depicted in pottery figurines and brick carvings from the era. Additionally, men’s clothing featuring plant-based patterns gained popularity during this period.

Beyond plant motifs, the flourishing cultivation of ornamental flowers in the Song Dynasty also influenced textile designs. Many of these patterns were inspired by the “Six Famous Flowers”—peonies, paeonia lactiflora, lotuses, plum blossoms, chrysanthemums, and orchids. Other frequently used floral motifs included hibiscus, camellias, crabapple blossoms, and hollyhocks, all chosen for their decorative appeal.

Song Dynasty plant motifs generally fell into two stylistic categories: abstract and realistic. The Northern Song period favored abstract patterns, while the Southern Song era saw a shift toward more naturalistic depictions. In the Northern Song, floral designs were often static, with a structured and somewhat formulaic layout. For example, textiles discovered in the Northern Song-era Changgan Temple underground chamber in Nanjing feature persimmon calyx floral patterns, arranged symmetrically in all directions. These motifs were highly stylized—so much so that the original flower shape was barely recognizable.

By the Southern Song period, winding vine floral patterns became more prevalent, emphasizing fluidity and natural movement in textile design.

The Song Dynasty also introduced a new decorative technique known as “flower within a flower” and “leaf within a flower.” For example, the peony heart jacquard fabric found in the tomb of Huang Sheng

(黄昇)features lotus flowers viewed from the side, with sharp petals as a mark, and plum blossoms viewed from above with five petals. These small, simple floral designs were used as “filling flowers.” Although small in size, they were vivid and graceful. Another example from Huang Sheng’s tomb is a hibiscus leaf jacquard fabric featuring plum blossoms, which showcases the distinctive aesthetic of the Song Dynasty. In these designs, flowers are filled within the large petals and leaves of winding vine motifs, adding intricate detail. These thematic motifs, imaginatively combined, represent a development in the Song Dynasty’s embellishment of textiles, a refined evolution of their floral patterns.

Ⅱ. Animal Motifs

As an extension of the Song Dynasty’s aesthetic style in flower-and-bird paintings, combinations of flowers, plants, and birds were also common motifs on textiles during this period. For example, a satin skirt from the tomb of the Zhou family in De’an (德安周氏), Jiangxi, features a swirling tree branch composition. The branches are decorated with leaves of varying sizes and shapes, and between the branches, there are images of the mythical phoenix (luan) and magpie. This motif, called the “spiraling leaf lovebird” pattern, is a prominent example of bird-themed designs.

Animal motifs are less common in Song Dynasty silk, with the most notable example being the lion on a “fortune” character pattern found on a brown silk fabric from the tomb of He Jiazao in Hengyang, Hunan. Despite some damage to the plant elements, the lion’s wide-eyed, astonished expression remains visible. Another noteworthy piece is from Huang Sheng’s tomb, where a dynamic image of a lion playing with a ball is woven on the edges of a silk fabric. While the depiction of the lion may seem somewhat unrefined, it clearly conveys the playful and lively character of the animal. Additionally, Huang Sheng’s tomb contains a rare tiger motif from the Song Dynasty, appearing on a piece of printed silk with a double tiger pattern. The pattern, being small in scale, doesn’t show the tiger’s face or its distinctive stripes.

Insect motifs began to gain popularity during the Song Dynasty, including images of butterflies, dragonflies, and bees. These motifs often use winding floral designs as a framework, with animals intertwined within, reflecting a strong Chinese aesthetic. Butterfly patterns, in particular, are more decorative due to the natural flower-like spots on their bodies and the elegant curves of their wings. For instance, a butterfly-shaped silver ornament found in a Song tomb in the Tea Garden Mountain of Fuzhou uses exaggerated arcs and curls to emphasize the antennae and details in the butterfly’s pattern. According to the History of the Song (《宋史·舆服志》), the emperor was entitled to use the five-clawed dragon, while princes could use the four-clawed dragon. However, it was common for dragon motifs to appear in the civilian realm as well. This trend can be attributed to the increasing secularization of Buddhism and Taoism during the Song Dynasty, which also led to the further popularization of dragon culture.

Ⅲ. Geometric Patterns

The geometric patterns on Song Dynasty silk as “extremely popular.” According to statistics by Zhao Feng (赵丰) and others, over 50 pieces of silk with geometric patterns have been unearthed from the Song Dynasty. Comparing this to the total of about 250 pieces of Song Dynasty jacquard silk fabrics, it’s evident that geometric patterns were quite prevalent in Song Dynasty silk. Among the unearthed silk fabrics, the geometric designs created using jacquard weaving techniques are mostly seen on fabrics like qi, ling, shi, and luo, (绮/damask、绫/twill brocade、絁/coarse thick plain silk、罗/gauze) which are plain-woven fabrics with the same color in both the warp and weft. Only a few pieces of jin (brocade) display geometric patterns using jacquard techniques. While Song Dynasty brocade is widely recognized, very few examples have been confirmed as actual Song Dynasty brocade, making it difficult to determine the color schemes of geometric patterns on Song brocade from the existing unearthed silks.

In Volume 14 of Treatise on Architectural Methods (《营造法式》 ), the Song scholar Li Jie (李诫) categorized patterns into six main types based on their primary themes. “华文” (luxurious patterns) was the largest category, interpreted as “beautiful patterns.” The second major category was “琐文” (minor patterns), which included six subtypes: 琐子 (small motifs), 蕈纹 (fungus patterns), 罗地龟纹 (tortoise-shell patterns), 四出 (patterns with four or six radiating lines), 剑环 (sword rings), and 曲水 (curved water patterns).

The cultural meanings of geometric patterns on Song Dynasty silk are not as numerous, but two typical examples stand out: The rectangular patterns on silk from the Southern Song tomb of Zhou Yu in Jin Tan are likely linked to the Southern Song’s imitation of Shang and Zhou bronze vessels. Another example, the clustered four-ball road patterns on silk found in the same tomb, are believed to reference the “毬路” mentioned in the Return to the Countryside(《归去来兮辞》)by Ouyang Xiu (欧阳修), which was used as a gift to the two imperial courts. The “毬路” pattern features a large circle at the center, which forms the core of the design. Surrounding it are smaller circles placed above, below, to the left, right, and at the corners, all interconnected in a continuous, circular pattern that expands outward. The design creates a square continuous pattern, with birds, animals, or geometric motifs placed between the large and small circles.

IV. Other Patterns

Silk textiles also feature patterns of human figures, objects, celestial phenomena, and text. In dyed textiles, human figures often depict children. For example, a fragment of peony, sunflower, and lotus child-patterned silk unearthed from the Hejiazao tomb in Hengyang features motifs of pomegranate, peach, lotus pods, and Buddha’s hand fruit. Various child figures, depicted sitting and holding tree branches, are interspersed within the design, creating a clear distinction between the main and secondary elements. The children have round faces and large heads, looking innocent and adorable.

Object patterns mainly include those commonly seen in Buddhism, such as the yingluo motif, which often combines with floral designs. These patterns were widespread in South Song clothing, and similar motifs were found in the Huangsheng and De’an Zhou tombs in Jiangxi. (黄昇墓、江西德安周氏墓)

Additionally, floral patterns also combine with auspicious symbols like the ruyi (decorative object ). Celestial patterns are mainly cloud motifs, with swirling, spiral-like clouds seen on silk unearthed from the Northern Song Changgan Temple. A popular motif in the Song Dynasty was the ruyi cloud pattern, consisting of seven cloud heads shaped like ruyi scepters, forming clusters of clouds that convey a sense of auspiciousness.

The trend of incorporating text patterns into Chinese silk began around the Han Dynasty. Examples include the “富” character lion playing with a pearl on a vine pattern found at the Hejiazao tomb in Hengyang, as well as the small golden dragon pattern found in the Northern Song Changgan Temple, where the four corners feature the characters “千” (thousand), “秋” (autumn), “万” (ten thousand), and “岁” (years), written neatly and filled with a lively, everyday spirit. The phrase “千秋万岁” is often used in the context of wishing for someone to live for a very long time, and it’s closely associated with longevity and immortality.

Summary

No matter the style or type of pattern, it’s all about what you personally love. The ancient Chinese used their wisdom to show the world their love for flowers, grass, birds in the sky, animals on the ground, and fish in the water. If you love something, wear it!

0 Comments