Attain an Ethereal and Floating Vibe with a Pibo

If you want to look a bit “fairy – like” in Hanfu style, you don’t necessarily have to be able to fly, but there’s one accessory you definitely can’t do without. Its name is: pibo. Just like many ladies nowadays always take a long silk scarf when they go traveling. When various photos of Chinese aunts wearing silk scarves are praised for their confidence and elegance, actually, the pibo was once a must – have item for every Chinese woman. This shows how much Chinese women love silk scarves.

Ⅰ. What is Pibo?

In the Tang Dynasty, hanfu pibo was called “pei zi (帔子)” or “ling jin (领巾)”, and after the Song Dynasty, it was known as “pibo”. It is a long, light – weighted and soft scarf in the shape of a floating ribbon. First, it is draped over the neck and shoulders, casually wrapped around the chest and arms, and finally hangs down beside the body.

During the Tang and Song dynasties, pibo was a commonly used accessory among women. Surprisingly, it was also seen on men’s ancient – style costumes. For example, the character Ming Ye (冥夜), the God of War in Till the End of the Moon, wore a pibo.

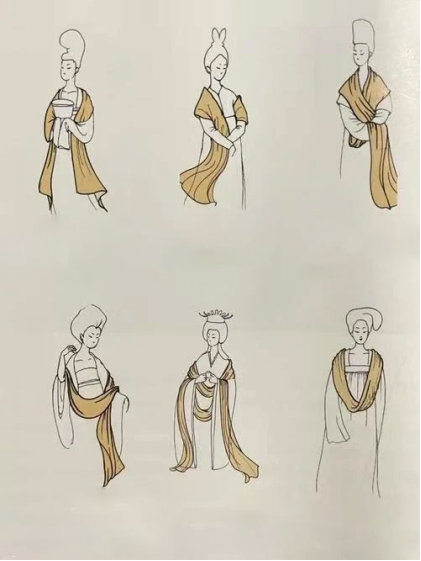

Pibo comes in a wide variety of colors and patterns. It is mainly made of thin silk and gauze. The two ends hang down and move with the wind, creating a light and elegant effect, serving a decorative purpose. Although pibo is just a simple piece of fabric, there are various ways to wear it. Some people drape it on the back, some across the chest, some tuck it into the skirt, and some tie it behind. A shorter pibo can be worn on the back, while a longer one can be wrapped around the arms. There are multiple ways to style it.

You may have seen pibo in various TV dramas. However, pibo was rarely seen before the Wei and Jin dynasties. Could it be a foreign import? Some scholars have proposed that pibo is not a native Chinese item, and this claim has long been a subject of debate. One theory is that it originated from Persia and was introduced to China via the Silk Road. The Persian habit of wearing pibo might have been influenced by Hellenization.

Another view is that it comes from China itself. Similar hanging ornaments to pibo have been found in the Warring States period and Han tombs (but their specific structures are unknown). So, the origin of pibo remains a controversial topic.

However, it doesn’t impede its extensive use in both Chinese and foreign creative works. Some of the images of immortals in Buddhist murals, as well as those in movies and TV shows that draw inspiration from them, along with ancient hanfu makeup and costume styles, all feature the pibo.

Anyway, the pibo has surely evolved its own history and unique characteristics in China. There are already hints of the pibo in the pottery figurines from the Wei and Jin dynasties. It was also known as “pei” or “pi” at that time, and it was relatively short, more resembling a scarf. As recorded in Shiming, “It is draped over the shoulders and back, not reaching down to the lower part of the body.” For instance, in Yu Xin’s poem A Poem Composed in Response to Prince Zhao’s Beauty in Spring (《奉和赵王美人春日诗》) during the Southern and Northern Dynasties, it says, “The hairpin on the headband of the hairpin for swaying moves, and the corner of the red pibo tilts.” Emperor Jianwen of the Liang Dynasty wrote in The Lament of a Courtesan (《倡妇怨》), “Casually draping the red pibo, a new charm emerges with the newly applied yellow makeup.”

There are already numerous images of the pibo in the murals of the Sui Dynasty and the cultural relics of the Tang Dynasty, making it a widely popular item. Such an accessory looks incredibly beautiful when paired with Hanfu. The love of women in the Tang Dynasty for the pibo can be evidenced by the record in Old Book of Tang: Records of Ritual Paraphernalia and Clothing Styles (《旧唐书·舆服志》), which states, “The social customs were extravagant. People did not abide by the regulations. They indulged in silk, brocade, and embroidery according to their own preferences. From the imperial palace to the common folk, they all imitated one another, with no distinction between the noble and the common.”

The pibo is usually made of light and thin silk materials like gauze, luo (罗, thin silk fabric), and ling (绫, silk fabric with a certain thickness). These materials are light, soft, and have excellent draping properties, giving a floating and lively appearance when worn. In terms of production techniques, methods such as brocade weaving and embroidery might be employed to adorn the pibo with various exquisite patterns, such as flowers, cloud motifs, dragons, and phoenixes, enhancing its magnificence and artistic value. The following picture shows the restoration of some patterns of the pibo in The Court Ladies Preparing Newly Woven Silk (《捣练图》).

Ⅱ. The Xiapei

The pibo indeed became less popular after the Song Dynasty, which is somewhat related to the aesthetic preferences of that time. Although the pibo fell out of favor, during the Song and Ming dynasties, it evolved into the “xiapei (霞帔)”, which became an important accessory for women’s formal attire. It was paired with a pendant at the bottom to balance its weight. Its shape was similar to that of the pibo, also in a long and narrow style. Usually, it was made in two layers and embroidered with patterns. When worn, it was draped around the neck from the back and then hung down in front of the chest. The lower end was fixed with a pendant made of gold or jade, so it didn’t flutter in the wind like the pibo. In a way, this can be considered an evolution of the pibo.

The Ming Dynasty was a peak period for the use of the xiapei. The use of the xiapei became institutionalized. Whether for empresses, consorts, or titled ladies, there were strict regulations regarding the color and patterns of the xiapei. The outfits shown in the following picture all belong to the empress, the highest rank, and they are indeed very magnificent.

The pibo, with its perfect combination of linear aesthetics and the beauty of the human body, especially when it flutters in the wind, is extremely dynamic. It has become a creation that briefly unleashes women’s aesthetic imagination, with its static and moving states complementing each other.

Ⅲ. Versatile Ways of Wearing

Let’s also talk about the ways to wear the pibo. Its function is not just for decoration. Generally, wearing it on the shoulders or draping it around the wrists gives off a Tang and Song dynasty clothing charm. Of course, in modern terms, wearing it on the body can also protect against the sun.

Wearing Method 1: For example, when wearing it on the shoulders, you can drape the pibo diagonally, and tuck one end a bit into the top of your skirt.

Wearing Method 2: As shown in the picture above, simply hanging it directly on the wrist is also very elegant and floating.

Wearing Method 3: Knot it in front of the chest, similar to the way the donors in the Dunhuang murals are dressed in the picture above.

There are also other ways of wearing, such as crossing it or wrapping it multiple times.

Of course, the pibo can also be used to cover the face to protect against wind and sand.

In addition, when you’re wearing Hanfu and find that the sleeves are too long and cumbersome, you can use a narrower pibo as a “panbo” (襻膊, a kind of sleeve – binding device). This allows you to roll up the large sleeves appropriately. A simple way to tie it is to make loops at both ends and put them around your wrists. Then you can bunch up the sleeves, which is very convenient.

The pibo also has a very practical use. You can twist it and use it as a clothes – drying rope. Also, you can simply drape it over your head. It’s quite nice to look like a “little noblewoman” with your head wrapped.

Summary

In short, having a hanfu pibo can be really handy in all sorts of situations, making our lives more convenient. If you’ve come up with any other amazing ways to use it, please leave a comment and share! We’re looking forward to your creative ideas!

0 Comments