Did Manicures Exist in China’s Tang Dynasty?

There’s a wide range of nail designs, from short – length and mid – long – length styles to minimalist, glittery, and vintage ones. Just like the world of fashion, the realm of nail art offers diverse options. But did you know? Nail – dyeing techniques existed during the Tang Dynasty in China. Similar to modern times, nail – dyeing back then was not only a way to showcase beauty but also a symbol of noble status, especially popular among aristocratic women. In ancient times, “koudan (蔻丹)” referred to dyed fingernails or the delicate hands with dyed nails. However, the colors available for nail – dyeing in ancient times were probably limited compared to the vast variety we have today.

Ⅰ. Nail – Dyeing

The garden balsam, commonly known as “nail – dyeing herb” or “maidens’ flower,” was a common material for nail – dyeing in ancient China. In those days, young women, often dressed in elegant hanfu, would engage in the delicate activity of nail – dyeing. The process was rather elaborate. One method involved pounding the flowers and leaves of the garden balsam finely in a small mortar. Then, a small amount of alum was added. After mixing, the resulting paste could be used to dye fingernails, which complemented their beautiful traditional Chinese outfit and added an extra touch of charm to their overall appearance.

According to Sequel to Miscellaneous Records from the Kuixin Era (《癸辛杂识续集》) written by Zhou Mi (周密) during the Southern Song Dynasty: “Crush the leaves of red garden balsams. Add a little alum to the mixture. First, clean your fingernails thoroughly. Then, apply the mixture to your nails and wrap them with a piece of fabric overnight. The initial color is light. Repeat the process three to five times, and the nails will turn as red as rouge. The color won’t wash off and can last for ten days. It only fades gradually when the nails start to fall off. Even elderly women in their seventies and eighties still dye their nails.”

There was another method. Shape silk floss into thin pieces similar in size to fingernails. Roll them up and soak them in the flower juice until they’re fully saturated. Then, stick the soaked silk floss onto the nails and secure it with string. Repeat this process three to five times. The resulting color could last for months without fading.

Noble ladies in the Tang Dynasty imperial court were really into nail – art. Yang Guifei, for example, was extremely fond of dyeing her nails. Her nail – dyeing habit inspired other palace women to imitate her, creating a popular trend. This fashion gradually spread from the imperial court to the aristocracy outside the palace and eventually reached the common people.

The Tang – Dynasty people truly adored well – groomed nails. Han Hou (韩翭), a poet of the Tang Dynasty, wrote a poem titled Ode to Hands to praise women’s hands: “Dressed in an elegant hanfu, her wrists are white, and the skin is as smooth as jade, with fingers like budding bamboo shoots. When she plays the zither or threads a needle, the tips of her fingers peek out from the flowing sleeves of her hanfu. Secretly, she carefully examines her fingers dyed with rouge; in the mirror, they gently complement the rosy glow of her cheeks. The beauty of her hanfu frames her delicate hands, adding to her allure. I recall sadly that I once saw her lift the embroidered curtain; vaguely, I remember her being escorted in a golden carriage, the fabric of her hanfu billowing gracefully in the breeze. In the back garden, she smiles and says to her companions, ‘I’ve picked wild rue and now I’m plucking flowers.’”

“Jade shoots” was used to praise and describe women’s long, slender fingernails, which resembled freshly sprouted, tender bamboo shoots.

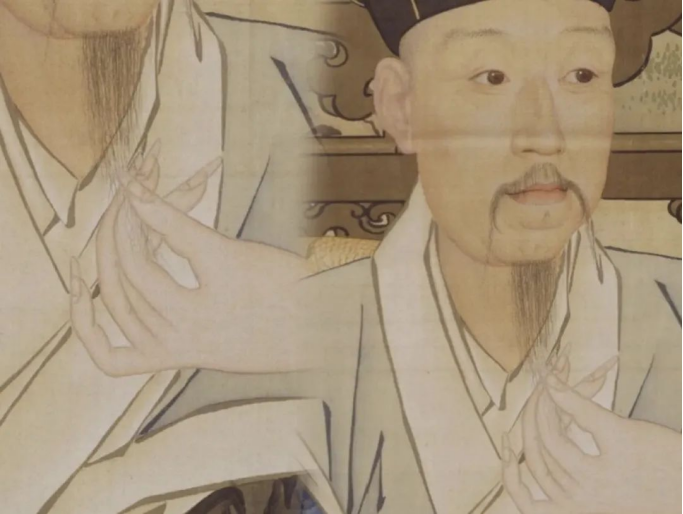

During the Tang Dynasty, it wasn’t just fashion – conscious girls who did their nails; stylish boys did too. In the mural of Vimalakirti Sutra on the northern wall of Cave 335 from the early Tang Dynasty in Dunhuang, there are two ministers. One of them has black – painted fingernails. Some scholars believe that the original color was red. Over time, due to oxidation, it gradually turned black.

Ⅱ. Nail Protectors

There was also a type of wearable “nail protector” similar to what we use today. Contrary to common belief, these weren’t exclusive to the Qing Dynasty. Some suggest they first appeared as early as the Warring States period (although this is speculative). Physical artifacts indicate that “nail – protecting sleeves ” or “finger sleeves” were in circulation during the Ming Dynasty.

There are two theories about the origin of these nail protectors. One is that they were used to prevent fingers from being scratched by the strings of musical instruments. The other is that since ancient women favored long nails, they crafted nail sleeves from hard materials like bone to protect their nails from breaking. These were called “claw – protectors.” In ancient times, the nail sleeves worn by noblewomen were incredibly luxurious, far more opulent than modern nail – art. They were often made of gold and silver, inlaid with various precious stones.

It appears that before the Qing Dynasty, finger sleeves were relatively rounded in shape. During the Qing Dynasty, especially in the imperial court, there was a preference for long, slender, and pointed designs. The TV drama Empresses in the Palace features a wide variety of nail – protector styles, showcasing their extravagance. One might wonder why these protectors were made so long. In the Qing Dynasty, long nail protectors signaled that the wearer didn’t need to engage in manual labor. They protected not just the nails but also the wearer’s social status. Nail protectors were made from various materials, including gold, silver, copper, as well as wood and animal bones.

Summary

Literati and refined scholars also frequently composed poems celebrating the beauty of women’s dyed nails. Zhang Hu wrote, “Ten delicate fingers are like jade shoots, tinged red.” Li He penned the lines, “The wax – lamp hangs high, illuminating the gauze; in the flower – chamber, red cinnabar is pounded at night.” These verses not only extolled the beauty of dyed nails but also helped popularize the nail – dyeing process as a symbol of beauty.

Surprisingly, men also once liked to grow long nails. However, their motive wasn’t for beauty. Instead, it was to prove that they didn’t have to do any menial work. Just as elaborate male hanfu signified social status, growing long nails was also a status symbol of the upper class. That’s why in some portraits, men are depicted with long nails, often paired with their elegant male hanfu. It turns out that the fashion for nail – art has remained consistent throughout history.

0 Comments