What Were the Female Officials in the Ming Dynasty Like?

In ancient China, it was extremely challenging for women to achieve great feats. However, there was a particular group that was an exception: female officials. Do you know that there were some Chinese women who didn’t have to confine themselves to the domestic sphere? Female officials were among them. Two Chinese dramas, Royal Feast by Yu Zheng and The Imperial Doctress by Li Guoli, tell stories centered around this group of female officials. The influence of these TV dramas is remarkable, and they have deeply impressed the audience. Some people wonder: Were female officials dressed in such elaborate hanfu, adorned with gold and silver? Let’s take a look at what real female officials were like.

Ⅰ. What Were Female Officials?

In ancient times, there were very few women in official positions. There was a group of women known as “female officials.” They held official ranks and were entitled to receive salaries. Their main role was to provide household management services for the royal family, and generally, they did not participate in political affairs.

When Emperor Taizu of the Ming Dynasty ordered the Ministry of Rites to formulate the system of palace officials, he referred to the systems of previous dynasties and established the Six Shang Bureaus and the Palace Rectification Department. “The bureaus were named Shanggong (尚宫), Shangyi (尚仪), Shangfu (尚服), Shangshi (尚食), Shangqin (尚寝), and Shanggong (尚功), and the department was called Gongzheng (宫正).” The duties of female officials generally fell into two categories: one was the regular responsibilities within the palace, and the other was the roles in the imperial court’s ceremonial systems.

The system of female officials in the Ming Dynasty was perfected during the Hongwu (洪武) period, so later generations basically took the regulations of the Hongwu period as the standard. We can understand that apart from being responsible for the daily life of the imperial harem, female officials also had to assist the empresses and concubines and set an example for the palace maids. There were numerous instances in the Ming Dynasty where female officials offered admonitions to the empress and concubines. Every time there was a lecture, the empress would lead the concubines to listen attentively.

In fact, regardless of the Tang, Song, or Ming dynasties, the clothing system of female officials was passed down. According to Ming Veritable Records and Collected Rites of the Great Ming Dynasty, they generally wore black gauze hats (some said they followed the Tang – style headwear), narrow – sleeved round – collared robes, leather belts around their waists, and black boots or arched shoes.

Judging from the portraits of female officials in the Song Dynasty, the ladies – in – waiting in the imperial harem were also influenced by popular customs such as wearing flowers in their hair to match their hanfu. Depending on their different jobs, it is speculated that the ladies – in – waiting in the imperial harem could also wear arched shoes and elaborate flower hairpins. In the Ming Dynasty, “The crowns and clothes of the palace women were of the same style as those in the Song Dynasty.”

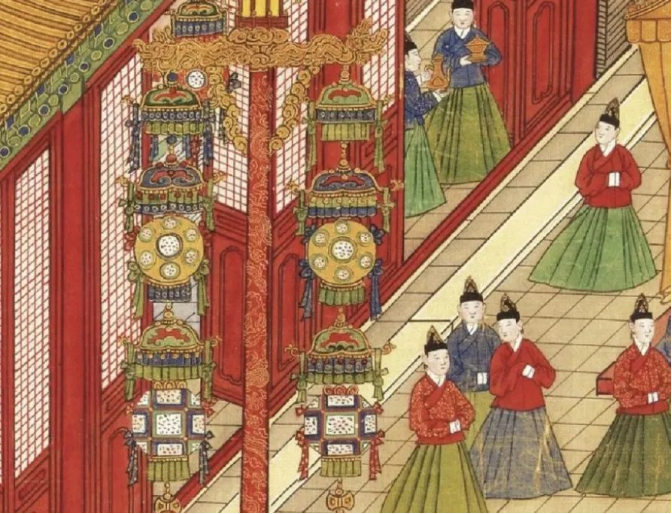

We often see the image of female officials in the Ming Dynasty wearing Di Ji (翟髻, a kind of headdress) with gold ornaments on their heads. This kind of decoration was for imperial consorts and noblewomen, and it actually looked out of place in the work attire of female officials. We can see this kind of palace women’s attire in the painting Emperor Xianzong Enjoying the Lantern Festival (《宪宗元宵行乐图》).

Ⅱ. The Attire of Female Officials

The materials of female officials’ clothing might also vary according to the four seasons. According to Liu Ruoyu’s Zhuo Zhongzhi (《酌中志》), palace ladies and eunuchs started wearing silk clothes on the fourth day of the third lunar month and switched to gauze clothes on the fourth day of the fourth lunar month. After the Qingming Festival, they began to put away leather clothes made from minks, squirrels, foxes, and other animals. On the fourth day of the ninth lunar month, they changed back to silk clothes. On the fourth day of the tenth lunar month, they wore ramie silk clothes. By November, as winter had already arrived in Beijing, they would wear earmuffs to keep warm.

During festive days, their attire would also change accordingly. On major festivals, there were days off, and female officials were allowed to change into festive clothing suitable for the occasion. For example, around the time of the Kitchen God Sacrifice before the Lunar New Year, they wore clothes with calabash pattern designs. During the Lantern Festival, they wore clothes with lantern pattern designs. On the seventh day of the seventh lunar month (the Qixi Festival), they wore clothes with the Magpie Bridge pattern, and on the Double Ninth Festival, they wore clothes with chrysanthemum pattern designs.

Ⅲ. The Selection of Female Officials

Entering the palace to serve as a female official meant that their families could be exempted from corvée labor, and the palace provided food and accommodation. This became a viable option for many impoverished women. The candidates were usually above 15 years old, with the majority falling between 30 and 40 years old. They were either unmarried or widowed. Moreover, in the Ming Dynasty, the selection criteria for female officials were different from those for palace maids. The initial selection criteria were “being able to read and write and proficient in arithmetic,” so there was basically no situation of misusing talents. However, palace maids could be promoted to female officials through palace education.

When selecting female officials in the early Ming Dynasty, not only did the chosen women need to have a certain level of cultural accomplishment, but there was also a preference for older women. Even if a woman was rather plain – looking but had excellent moral character, talent, and knowledge, she could still be selected. Young girls under 20 years old were either candidates for the emperor’s concubines or were selected for daily service work such as cleaning and washing, and there was no requirement for them to be literate. The selection of female officials mainly focused on unmarried or widowed women above 20 years old, and even above 30 years old. Judging from the established selection criteria, female officials did not meet the conditions to become the emperor’s concubines. The female official system was not part of the imperial consort system. Even if there were cases of female officials serving the emperor, they were considered rare exceptions.

As depicted in the TV drama Royal Feast, in the Ming Dynasty, the imperial court would look for potential empresses and concubines among the common people. There was a chance that female officials who entered the palace due to their virtue and talent could become empresses, concubines, or crown princesses. However, most female officials, having understood history after becoming officials, also had the courage to realize that “relying on one’s beauty to serve others would not last long.” Female officials earned the respect of the palace staff with their noble character, so they were generally strict and self – disciplined, setting an example with their own behavior.

For instance, Huang Weide (黄惟德), a female official, was selected as a female official in the 22nd year of the Hongwu reign. She had always been pure and adhered to the etiquette between the sovereign and the subject. In the 2nd year of the Yongle reign, a female official named Wang was recommended to the emperor by an imperial concubine, and the emperor was interested. However, Wang declined on the grounds that she was a widow, which demonstrated her chastity and moral integrity. Nevertheless, there were still some exceptional cases where some female relatives who could not be given an official title were arranged to be female officials.

Moreover, most female officials came from decent backgrounds and had no connections with the powerful eunuchs or noble forces. They would not collude with officials or disrupt the order of the imperial harem. It is evident that the selection system for female officials in the Ming Dynasty was very strict, which is somewhat similar to the recruitment process of a modern company. That is: initial interview—second interview—entry medical examination—probation period—official employment.

Senior female officials were known as “Lady Gentlemen,” “Lady Historians,” or “Lady Scholars.” In addition, female officials were granted imperial robes. For example, Huang Weide, whom we mentioned earlier, was highly regarded for her both virtue and talent. She served as the director of the Shangfu Bureau and was awarded the imperial mandate of the fifth rank.

The fifth rank was already considered the highest position among female officials (except in special cases). It can be seen that the rulers of the Ming Dynasty intended for them to only manage the daily affairs of food, clothing, housing, and transportation in the imperial palace, preventing the potential for them to interfere in government affairs or cause internal unrest. The imperial robes were adorned with rank badges symbolizing social status, and they were grand ceremonial costumes. Generally, when on duty in daily life, female officials still wore the official hanfu uniforms mentioned before.

Female officials had the option to retire and return to their hometowns, or they could choose to stay in the palace. Some even formed “companionate marriages” within the palace. Returning to their hometowns brought honor to their families, and they would continue to receive a salary to support themselves. One of the female officials who stayed in the palace for a long time was Lady Huang during the Xuande period. She retired and returned to her hometown at the age of 75. By then, she had few relatives left at home, but the imperial family treated her with great courtesy. So, although she seemed to be alone for most of her life, in terms of treatment, she was actually quite well – off.

Summary

It is hoped that the costumes, makeup, and props in various ancient – themed TV dramas can be more refined and perfected. After all, the Ming Dynasty was a period when the Chinese traditional dress system and its records were quite comprehensive. Isn’t it sufficient to draw inspiration from the aesthetic standards of our Chinese ancestors?

0 Comments